Marvel Comics

Marvel Comics logo introduced in 2024 | |

| Parent company |

|

|---|---|

| Status | Active |

| Founded |

|

| Founder | Martin Goodman |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Headquarters location | 135 W. 50th Street, Manhattan, New York City |

| Distribution |

|

| Key people |

|

| Publication types | List of publications |

| Fiction genres | |

| Imprints | imprint list |

| Official website | marvel |

Marvel Comics is a New York City-based comic book publisher, a property of The Walt Disney Company since December 31, 2009, and a subsidiary of Disney Publishing Worldwide since March 2023. Marvel was founded in 1939 by Martin Goodman as Timely Comics,[3] and by 1951 had generally become known as Atlas Comics. The Marvel era began in August 1961 with the launch of The Fantastic Four and other superhero titles created by Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, and numerous others. The Marvel brand, which had been used over the years and decades, was solidified as the company's primary brand.

Marvel counts among its characters such well-known superheroes as Spider-Man, Iron Man, Wolverine, Captain America, Black Widow, Thor, Hulk, Daredevil, Doctor Strange, Black Panther, Captain Marvel, and Deadpool, as well as popular superhero teams such as the Avengers, X-Men, Fantastic Four, and Guardians of the Galaxy. Its stable of well-known supervillains includes Doctor Doom, Magneto, Green Goblin, Kingpin, Red Skull, Loki, Ultron, Thanos, Kang the Conqueror, Venom, and Galactus. Most of Marvel's fictional characters operate in a single reality known as the Marvel Universe, with most locations mirroring real-life places; many major characters are based in New York City.[4] Additionally, Marvel has published several licensed properties from other companies. This includes Star Wars comics, twice from 1977 to 1987, and again since 2015.

History

Timely Publications

Pulp-magazine publisher Martin Goodman created the company later known as Marvel Comics under the name Timely Publications in 1939.[5][6] Goodman, who had started with a Western pulp in 1933, was expanding into the emerging—and by then already highly popular—new medium of comic books. Launching his new line from his existing company's offices at 330 West 42nd Street, New York City, he officially held the titles of editor, managing editor, and business manager, with Abraham Goodman (Martin's brother)[7] officially listed as publisher.[6]

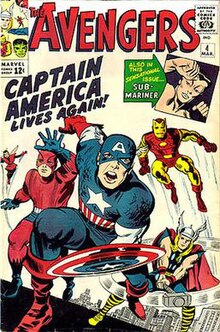

Timely's first publication, Marvel Comics #1 (cover dated Oct. 1939), included the first appearance of Carl Burgos' android superhero the Human Torch, and the first appearances of Bill Everett's anti-hero Namor the Sub-Mariner,[8] among other features.[5] The issue was a great success; it and a second printing the following month sold a combined nearly 900,000 copies.[9] While its contents came from an outside packager, Funnies, Inc.,[5] Timely had its own staff in place by the following year. The company's first true editor, writer-artist Joe Simon, teamed with artist Jack Kirby to create one of the first patriotically themed superheroes,[10] Captain America, in Captain America Comics #1 (March 1941). It, too, proved a hit, with sales of nearly one million.[9] Goodman formed Timely Comics, Inc., beginning with comics cover-dated April 1941 or Spring 1941.[3][11]

While no other Timely character would achieve the success of these three characters, some notable heroes—many of which continue to appear in modern-day retcon appearances and flashbacks—include the Whizzer, Miss America, the Destroyer, the original Vision, and the Angel. Timely also published one of humor cartoonist Basil Wolverton's best-known features, "Powerhouse Pepper",[12][13] as well as a line of children's talking animal comics featuring characters like Super Rabbit and the duo Ziggy Pig and Silly Seal.

Goodman hired his wife's 16-year-old cousin,[14] Stanley Lieber, as a general office assistant in 1939.[15] When editor Simon left the company in late 1941,[16] Goodman made Lieber—by then writing pseudonymously as "Stan Lee"—interim editor of the comics line, a position Lee kept for decades except for three years during his military service in World War II. Lee wrote extensively for Timely, contributing to a number of different titles.

Goodman's business strategy involved having his various magazines and comic books published by a number of corporations all operating out of the same office and with the same staff.[3] One of these shell companies through which Timely Comics was published was named Marvel Comics by at least Marvel Mystery Comics #55 (May 1944). As well, some comics' covers, such as All Surprise Comics #12 (Winter 1946–47), were labeled "A Marvel Magazine" many years before Goodman would formally adopt the name in 1961.[17] The company begin identifying the group of its comic division as Marvel Comic Group, on some comics cover-dated November 1948, when the company set up an in-house editorial board to compete with the likes of DC and Fawcett, even though the legal name is still Timely.[18][19][20]

Magazine Management / Atlas Comics

The post-war American comic market saw superheroes falling out of fashion.[21] Goodman's comic book line dropped them for the most part and expanded into a wider variety of genres than even Timely had published, featuring horror, Westerns, humor, talking animal, men's adventure-drama, giant monster, crime, and war comics, and later adding jungle books, romance titles, espionage, and even medieval adventure, Bible stories and sports.

Goodman began using the globe logo of the Atlas News Company, the newsstand-distribution company he owned,[22] on comics cover-dated November 1951 even though another company, Kable News, continued to distribute his comics through the August 1952 issues.[23] This globe branding united a line put out by the same publisher, staff and freelancers through 59 shell companies, from Animirth Comics to Zenith Publications.[24]

Atlas, rather than innovate, took a proven route of following popular trends in television and films—Westerns and war dramas prevailing for a time, drive-in film monsters another time—and even other comic books, particularly the EC horror line.[25] Atlas also published a plethora of children's and teen humor titles, including Dan DeCarlo's Homer the Happy Ghost (similar to Casper the Friendly Ghost) and Homer Hooper (à la Archie Andrews). Atlas unsuccessfully attempted to revive superheroes from late 1953 to mid-1954, with the Human Torch (art by Syd Shores and Dick Ayers, variously), the Sub-Mariner (drawn and most stories written by Bill Everett), and Captain America (writer Stan Lee, artist John Romita Sr.). Atlas did not achieve any breakout hits and, according to Stan Lee, survived chiefly because it produced work quickly, cheaply, and at a passable quality.[26]

In 1957, Goodman switched distributors to the American News Company—which shortly afterward lost a Justice Department lawsuit and discontinued its business.[27] Atlas was left without distribution and was forced to turn to Independent News, the distribution arm of its biggest rival, National (DC) Comics, which imposed draconian restrictions on Goodman's company. As then-Atlas editor Stan Lee recalled in a 1988 interview, "[We had been] turning out 40, 50, 60 books a month, maybe more, and ... suddenly we went ... to either eight or 12 books a month, which was all Independent News Distributors would accept from us."[28] The company was briefly renamed to Goodman Comics in 1957 under the distribution deal with Independent News.[29]

Marvel Comics

The first modern comic books under the Marvel Comics brand were the science-fiction anthology Journey into Mystery #69 and the teen-humor title Patsy Walker #95 (both cover dated June 1961), which each displayed an "MC" box on its cover.[30] Then, in the wake of DC Comics' success in reviving superheroes in the late 1950s and early 1960s, particularly with the Flash, Green Lantern, Batman, Superman, Wonder Woman, Green Arrow, and other members of the team the Justice League of America, Marvel followed suit.[n 1]

In 1961, writer-editor Stan Lee revolutionized superhero comics by introducing superheroes designed to appeal to older readers than the predominantly child audiences of the medium, thus ushering what Marvel later called the Marvel Age of Comics.[31] Modern Marvel's first superhero team, the titular stars of The Fantastic Four #1 (Nov. 1961),[32] broke convention with other comic book archetypes of the time by squabbling, holding grudges both deep and petty, and eschewing anonymity or secret identities in favor of celebrity status. Subsequently, Marvel comics developed a reputation for focusing on characterization and adult issues to a greater extent than most superhero comics before them, a quality which the new generation of older readers appreciated.[33] This applied to The Amazing Spider-Man title in particular, which turned out to be Marvel's most successful book. Its young hero suffered from self-doubt and mundane problems like any other teenager, something with which many readers could identify.[34]

Stan Lee and freelance artist and eventual co-plotter Jack Kirby's Fantastic Four originated in a Cold War culture that led their creators to revise the superhero conventions of previous eras to better reflect the psychological spirit of their age.[35] Eschewing such comic book tropes as secret identities and even costumes at first, having a monster as one of the heroes, and having its characters bicker and complain in what was later called a "superheroes in the real world" approach, the series represented a change that proved to be a great success.[36]

Marvel often presented flawed superheroes, freaks, and misfits—unlike the perfect, handsome, athletic heroes found in previous traditional comic books. Some Marvel heroes looked like villains and monsters such as the Hulk and the Thing. This naturalistic approach even extended into topical politics. Comics historian Mike Benton also noted:

In the world of [rival DC Comics'] Superman comic books, communism did not exist. Superman rarely crossed national borders or involved himself in political disputes.[37] From 1962 to 1965, there were more communists [in Marvel Comics] than on the subscription list of Pravda. Communist agents attack Ant-Man in his laboratory, red henchmen jump the Fantastic Four on the moon, and Viet Cong guerrillas take potshots at Iron Man.[38]

All these elements struck a chord with the older readers, including college-aged adults. In 1965, Spider-Man and the Hulk were both featured in Esquire magazine's list of 28 college campus heroes, alongside John F. Kennedy and Bob Dylan.[39] In 2009, writer Geoff Boucher reflected that,

Superman and DC Comics instantly seemed like boring old Pat Boone; Marvel felt like The Beatles and the British Invasion. It was Kirby's artwork with its tension and psychedelia that made it perfect for the times—or was it Lee's bravado and melodrama, which was somehow insecure and brash at the same time?[40]

In addition to Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four, Marvel began publishing further superhero titles featuring such heroes and antiheroes as the Hulk, Thor, Ant-Man, Iron Man, the X-Men, Daredevil, the Inhumans, Black Panther, Doctor Strange, Captain Marvel and the Silver Surfer, and such memorable antagonists as Doctor Doom, Magneto, Galactus, Loki, the Green Goblin, and Doctor Octopus, all existing in a shared reality known as the Marvel Universe, with locations that mirror real-life cities such as New York, Los Angeles and Chicago.

Marvel even lampooned itself and other comics companies in a parody comic, Not Brand Echh (a play on Marvel's dubbing of other companies as "Brand Echh", à la the then-common phrase "Brand X").[41]

Originally, the company's publications were branded by a minuscule "Mc" on the upper right-hand corner of the covers. However, artist/writer Steve Ditko put a larger masthead picture of the title character of The Amazing Spider-Man on the upper left-hand corner on issue #2 that included the series' issue number and price. Lee appreciated the value of this visual motif and adapted it for the company's entire publishing line. This branding pattern, being typically either a full-body picture of the characters' solo titles or a collection of the main characters' faces in ensemble titles, would become standard for Marvel for decades.[42]

Cadence Industries ownership

In 1968, while selling 50 million[citation needed] comic books a year, company founder Goodman revised the constraining distribution arrangement with Independent News he had reached under duress during the Atlas years, allowing him now to release as many titles as demand warranted.[22] Late that year, he sold Marvel Comics and its parent company, Magazine Management, to the Perfect Film & Chemical Corporation (later known as Cadence Industries), though he remained as publisher.[43] In 1969, Goodman finally ended his distribution deal with Independent by signing with Curtis Circulation Company.[22]

In 1971, the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare approached Marvel Comics editor-in-chief Stan Lee to do a comic book story about drug abuse. Lee agreed and wrote a three-part Spider-Man story portraying drug use as dangerous and unglamorous. However, the industry's self-censorship board, the Comics Code Authority, refused to approve the story because of the presence of narcotics, deeming the context of the story irrelevant. Lee, with Goodman's approval, published the story regardless in The Amazing Spider-Man #96–98 (May–July 1971), without the Comics Code seal. The market reacted well to the storyline, and the CCA subsequently revised the Code the same year.[44]

Goodman retired as publisher in 1972 and installed his son, Chip, as publisher.[45] Shortly thereafter, Lee succeeded him as publisher and also became Marvel's president[45] for a brief time.[46] During his time as president, he appointed his associate editor, prolific writer Roy Thomas, as editor-in-chief. Thomas added "Stan Lee Presents" to the opening page of each comic book.[45]

A series of new editors-in-chief oversaw the company during another slow time for the industry. Once again, Marvel attempted to diversify, and with the updating of the Comics Code published titles themed to horror (The Tomb of Dracula), martial arts (Shang-Chi: Master of Kung Fu), sword-and-sorcery (Conan the Barbarian in 1970,[47] Red Sonja), satire (Howard the Duck) and science fiction (2001: A Space Odyssey, "Killraven" in Amazing Adventures, Battlestar Galactica, Star Trek, and, late in the decade, the long-running Star Wars series). Some of these were published in larger-format black and white magazines, under its Curtis Magazines imprint.

Marvel was able to capitalize on its successful superhero comics of the previous decade by acquiring a new newsstand distributor and greatly expanding its comics line. Marvel pulled ahead of rival DC Comics in 1972, during a time when the price and format of the standard newsstand comic were in flux.[48] Goodman increased the price and size of Marvel's November 1971 cover-dated comics from 15 cents for 36 pages total to 25 cents for 52 pages. DC followed suit, but Marvel the following month dropped its comics to 20 cents for 36 pages, offering a lower-priced product with a higher distributor discount.[49]

In 1973, Perfect Film & Chemical renamed itself as Cadence Industries and renamed Magazine Management as Marvel Comics Group.[50] Goodman, now disconnected from Marvel, set up a new company called Seaboard Periodicals in 1974, reviving Marvel's old Atlas name for a new Atlas Comics line, but this lasted only a year and a half.[51] In the mid-1970s a decline of the newsstand distribution network affected Marvel. Cult hits such as Howard the Duck fell victim to the distribution problems, with some titles reporting low sales when in fact the first specialty comic book stores resold them at a later date.[citation needed] But by the end of the decade, Marvel's fortunes were reviving, thanks to the rise of direct market distribution—selling through those same comics-specialty stores instead of newsstands.

Marvel ventured into audio in 1975 with a radio series and a record, both had Stan Lee as narrator. The radio series was Fantastic Four. The record was Spider-Man: Rock Reflections of a Superhero concept album for music fans.[52]

Marvel held its own comic book convention, Marvelcon '75, in spring 1975, and promised a Marvelcon '76. At the 1975 event, Stan Lee used a Fantastic Four panel discussion to announce that Jack Kirby, the artist co-creator of most of Marvel's signature characters, was returning to Marvel after having left in 1970 to work for rival DC Comics.[54] In October 1976, Marvel, which already licensed reprints in different countries, including the UK, created a superhero specifically for the British market. Captain Britain debuted exclusively in the UK, and later appeared in American comics.[55] During this time, Marvel and the Iowa-based Register and Tribune Syndicate launched a number of syndicated comic strips — The Amazing Spider-Man, Howard the Duck, Conan the Barbarian, and The Incredible Hulk. None of the strips lasted past 1982, except for The Amazing Spider-Man, which is still being published.

In 1978, Jim Shooter became Marvel's editor-in-chief. Although a controversial personality, Shooter cured many of the procedural ills at Marvel, including repeatedly missed deadlines. During Shooter's nine-year tenure as editor-in-chief, Chris Claremont and John Byrne's run on the Uncanny X-Men and Frank Miller's run on Daredevil became critical and commercial successes.[56] Shooter brought Marvel into the rapidly evolving direct market,[57] institutionalized creator royalties, starting with the Epic Comics imprint for creator-owned material in 1982; introduced company-wide crossover story arcs with Contest of Champions and Secret Wars; and in 1986 launched the ultimately unsuccessful New Universe line to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Marvel Comics imprint. Star Comics, a children-oriented line differing from the regular Marvel titles, was briefly successful during this period, although hampered by legal action by the owners of the recently defunct Harvey Comics for purposefully plagiarizing their house style.[58]

Marvel Entertainment Group ownership

In 1986, Marvel's parent, Marvel Entertainment Group, was sold to New World Entertainment, which within three years sold it to MacAndrews and Forbes, owned by Revlon executive Ronald Perelman in 1989. In 1991 Perelman took MEG public. Following the rapid rise of this stock, Perelman issued a series of junk bonds that he used to acquire other entertainment companies, secured by MEG stock.[59]

Marvel earned a great deal of money with their 1980s children's comics imprint Star Comics[citation needed] and they earned a great deal more money and worldwide success during the comic book boom of the early 1990s, launching the successful 2099 line of comics set in the future (Spider-Man 2099, etc.) and the creatively daring though commercially unsuccessful Razorline imprint of superhero comics created by novelist and filmmaker Clive Barker.[60][61] In 1990, Marvel began selling Marvel Universe Cards with trading card maker SkyBox International. These were collectible trading cards that featured the characters and events of the Marvel Universe. The 1990s saw the rise of variant covers, cover enhancements, swimsuit issues, and company-wide crossovers that affected the overall continuity of the Marvel Universe.

In early 1992, seven of Marvel’s prized artists — Todd McFarlane (known for his work on Spider-Man), Jim Lee (X-Men), Rob Liefeld (X-Force), Marc Silvestri (Wolverine), Erik Larsen (The Amazing Spider-Man), Jim Valentino (Guardians of the Galaxy), and Whilce Portacio (Uncanny X-Men) — left to form Image Comics[62] in a deal brokered by Malibu Comics' owner Scott Mitchell Rosenberg.[63] Three years later, on November 3, 1994, Rosenberg sold Malibu to Marvel.[64][65][66] In purchasing Malibu, Marvel now owned computer coloring technology that had been developed by Rosenberg,[67] and also integrated the Ultraverse line of comics and the Genesis Universe into Marvel's multiverse.[68] Earlier that year, the company secured a deal with Harvey Comics, whereas Marvel took on the publishing and distribution of Harvey's titles.[69]

In late 1994, Marvel acquired the comic book distributor Heroes World Distribution to use as its own exclusive distributor.[70] As the industry's other major publishers made exclusive distribution deals with other companies, the ripple effect resulted in the survival of only one other major distributor in North America, Diamond Comic Distributors Inc.[71][72] Then, by the middle of the decade, the industry had slumped, and in December 1996 MEG filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.[59] In early 1997, when Marvel's Heroes World endeavor failed, Diamond also forged an exclusive deal with Marvel[73]—giving the company its own section of its comics catalog Previews.[74]

Marvel in the early to mid-1990s expanded their entries in other media, including Saturday-morning cartoons and various comics collaborations to explore new genres. In 1992, they released the X-Men: The Animated Series which was aired on Fox Kids, they later released Spider-Man: The Animated Series on the network as well. In 1993, Marvel teamed up with Thomas Nelson to create Christian media genre comics, including a Christian superhero named The Illuminator, they made adaptions of Christian novels too, including In His Steps, The Screwtape Letters, and The Pilgrim's Progress.[75][76] In 1996, Marvel had some of its titles participate in "Heroes Reborn", a crossover that allowed Marvel to relaunch some of its flagship characters such as the Avengers and the Fantastic Four, and outsource them to the studios of two of the former Marvel artists turned Image Comics founders, Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld. The relaunched titles, which saw the characters transported to a parallel universe with a history distinct from the mainstream Marvel Universe, were a solid success amidst a generally struggling industry.[77]

Marvel Enterprises

In 1997, Toy Biz bought Marvel Entertainment Group to end the bankruptcy, forming a new corporation, Marvel Enterprises.[59] With his business partner Avi Arad, publisher Bill Jemas, and editor-in-chief Bob Harras, Toy Biz co-owner Isaac Perlmutter helped stabilize the comics line.[78]

In 1998, the company launched the imprint Marvel Knights, taking place “with reduced [Marvel] continuity,” according to one history, with better production quality.[79] The imprint was helmed by soon-to-become editor-in-chief Joe Quesada; it featured tough, gritty stories showcasing such characters as the Daredevil, the Inhumans, and Black Panther.[79][80][81][82]

With the new millennium, Marvel Comics emerged from bankruptcy and again began diversifying its offerings. X-Force #116 X-Force #119 (October 2001) was the first Marvel Comics title since The Amazing Spider-Man #96–98 in 1971 to not have the Comics Code Authority (CCA) approval seal, due to the violence depicted in the issue. The CCA, which governed the content of American comic books, rejected the issue, requiring that changes be made. Instead, Marvel simply stopped submitting comics to the CCA.[83][84][85] It then established its own Marvel Rating System for comics.[86][87] Marvel also created new imprints, such as MAX (an explicit-content line)[88][89] and Marvel Adventures (developed for child audiences).[90][91] The company also created an alternate universe imprint, Ultimate Marvel, that allowed the company to reboot its major titles by revising and updating its characters to introduce to a new generation.[92]

Some of the company's properties were adapted into successful film franchises, such as the Men in Black film series (which was based on a Malibu book), starting in 1997, the Blade film series, starting in 1998, the X-Men film series, starting in 2000, and the highest grossing series, Spider-Man, beginning in 2002.[93]

Marvel's Conan the Barbarian title was canceled in 1993 after 275 issues, while the Savage Sword of Conan magazine had lasted 235 issues. Marvel published additional titles including miniseries until 2000 for a total of 650 issues. Conan was picked up by Dark Horse Comics three years later.[47]

In a cross-promotion, the November 1, 2006, episode of the CBS soap opera Guiding Light, titled "She's a Marvel", featured the character Harley Davidson Cooper (played by Beth Ehlers) as a superheroine named the Guiding Light.[94] The character's story continued in an eight-page backup feature, "A New Light", that appeared in several Marvel titles published November 1 and 8.[95] Also that year, Marvel created a wiki on its Web site.[96]

In late 2007 the company launched Marvel Digital Comics Unlimited, a digital archive of over 2,500 back issues available for viewing, for a monthly or annual subscription fee.[97] At the December 2007 the New York Anime Fest, the company announcement that Del Rey Manga would published two original English language Marvel manga books featuring the X-Men and Wolverine to hit the stands in spring 2009.[98]

In 2009 Marvel Comics closed its Open Submissions Policy, in which the company had accepted unsolicited samples from aspiring comic book artists, saying the time-consuming review process had produced no suitably professional work.[99] The same year, the company commemorated its 70th anniversary, dating to its inception as Timely Comics, by issuing the one-shot Marvel Mystery Comics 70th Anniversary Special #1 and a variety of other special issues.[100][101]

Disney conglomerate unit (2009–present)

On August 31, 2009, The Walt Disney Company announced it would acquire Marvel Comics' parent corporation, Marvel Entertainment, for a cash and stock deal worth approximately $4 billion, which if necessary would be adjusted at closing, giving Marvel shareholders $30 and 0.745 Disney shares for each share of Marvel they owned.[102][103] As of 2008, Marvel and its major competitor DC Comics shared over 80% of the American comic-book market.[104]

As of September 2010, Marvel switched its bookstore distribution company from Diamond Book Distributors to Hachette Distribution Services.[105] Marvel moved its office to the Sports Illustrated Building in October 2010.[106]

Marvel relaunched the CrossGen imprint, owned by Disney Publishing Worldwide, in March 2011.[107] Marvel and Disney Publishing began jointly publishing Disney/Pixar Presents magazine that May.[108]

Marvel discontinued its Marvel Adventures imprint in March 2012,[109] and replaced them with a line of two titles connected to the Marvel Universe TV block.[110] Also in March, Marvel announced its Marvel ReEvolution initiative that included Infinite Comics,[111] a line of digital comics, Marvel AR, a software application that provides an augmented reality experience to readers and Marvel NOW!, a relaunch of most of the company's major titles with different creative teams.[112][113] Marvel NOW! also saw the debut of new flagship titles including Uncanny Avengers and All-New X-Men.[114]

In April 2013, Marvel and other Disney conglomerate components began announcing joint projects. With ABC, a Once Upon a Time graphic novel was announced for publication in September.[115] With Disney, Marvel announced in October 2013 that in January 2014 it would release its first title under their joint "Disney Kingdoms" imprint "Seekers of the Weird", a five-issue miniseries.[116] On January 3, 2014, fellow Disney subsidiary Lucasfilm announced that as of 2015, Star Wars comics would once again be published by Marvel.[117]

Following the events of the company-wide crossover "Secret Wars" in 2015, a relaunched Marvel universe began in September 2015, called the All-New, All-Different Marvel.[118]

Marvel Legacy was the company's Fall 2017 relaunch branding, which began that September. Books released as part of that initiative featured lenticular variant covers that required comic book stores to double their regular issue order to be able to order the variants. The owner of two Comix Experience stores complained about requiring retailers to purchase an excess of copies featuring the regular cover, which they would not be able to sell in order to acquire the more sought-after variant. Marvel responded to these complaints by rescinding these ordering requirements on newer series, but maintained it on more long-running titles like Invincible Iron Man. As a result, MyComicShop.com and at least 70 other comic book stores boycotted these variant covers.[119] Despite the release of Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, Logan, Thor: Ragnarok, and Spider-Man: Homecoming in theaters, none of those characters' titles featured in the top 10 sales and the Guardians of the Galaxy comic book series was canceled.[120] Conan Properties International announced on January 12, 2018, that Conan would return to Marvel in early 2019.[47]

On March 1, 2019, Serial Box, a digital book platform, announced a partnership with Marvel, in which they would publish new and original stories tied to a number of Marvel's popular franchises.[121]

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, from March to May 2020, Marvel and its distributor Diamond Comic Distributors stopped producing and releasing new comic books.[122][123][124]

On March 25, 2021, Marvel Comics announced that they planned to shift their direct market distribution for monthly comics and graphic novels from Diamond Comic Distributors to Penguin Random House. The change was scheduled to start on October 1, 2021, in a multi-year partnership. The arrangement would still allow stores the option to order comics from Diamond, but Diamond would be acting as a wholesaler rather than distributor.[1]

On March 29, 2023, as a part of a corporate restructuring to fold Marvel Entertainment into The Walt Disney Company, Marvel Comics was transferred to Disney Publishing Worldwide.[125][126]

In June 2024, Marvel unveiled a new logo for Marvel Comics, similar in style to the logos for Marvel Studios and Marvel Studios Animation. This logo was meant to be used for more "corporate" purposes and on new social media channels for Marvel Comics, and would not appear on comics themselves.[127][128]

Officers

- Michael Z. Hobson, executive vice president;[129] Marvel Comics Group vice-president (1986)[130]

- Stan Lee, chairman and publisher (1986)[130]

- Joseph Calamari, executive vice president (1986)[130]

- Jim Shooter, vice president and editor-in-chief (1986)[130]

Publishers

- (Abraham Goodman, 1939[6])

- Martin Goodman, 1939–1972[45]

- Charles "Chip" Goodman, 1972[45]

- Stan Lee, 1972 – October 1996[45][46][129]

- Shirrel Rhoades, October 1996 – October 1998[129]

- Winston Fowlkes, February 1998 – November 1999[129]

- Bill Jemas, February 2000 – 2003[129]

- Dan Buckley, 2003[131] — January 2017[132][133]

- John Nee, January 2018 — present[132]

Editors-in-chief

Marvel's chief editor originally held the title of "editor". This head editor's title later became "editor-in-chief". Joe Simon was the company's first true chief-editor, with publisher Martin Goodman, who had served as titular editor only and outsourced editorial operations.

In 1994 Marvel briefly abolished the position of editor-in-chief, replacing Tom DeFalco with five group editors-in-chief. As Carl Potts described the 1990s editorial arrangement:

In the early '90s, Marvel had so many titles that there were three Executive Editors, each overseeing approximately one-third of the line. Bob Budiansky was the third Executive Editor [following the previously promoted Mark Gruenwald and Potts]. We all answered to Editor-in-Chief Tom DeFalco and Publisher Mike Hobson. All three Executive Editors decided not to add our names to the already crowded credits on the Marvel titles. Therefore it wasn't easy for readers to tell which titles were produced by which Executive Editor … In late '94, Marvel reorganized into a number of different publishing divisions, each with its own Editor-in-Chief.[134]

Marvel reinstated the overall editor-in-chief position in 1995 with Bob Harras.

|

Editor

|

Editor-in-chief

|

Executive Editors

Originally called associate editor when Marvel's chief editor just carried the title of editor, the title of the second-highest editorial position became executive editor under the chief editor title of editor-in-chief. The title of associate editor later was revived under the editor-in-chief as an editorial position in charge of few titles under the direction of an editor and without an assistant editor.

Associate Editor

- Jim Shooter, January 5, 1976 – January 2, 1978[136]

Executive Editor

- Tom DeFalco, 1983–1987

- Mark Gruenwald, 1987–1991; Senior Executive Editor: 1991–1995

- Carl Potts, Epic Comics Executive Editor, 1989–1995[134]

- Bob Budiansky, Special Projects Executive Editor, 1991–1995[134]

- Bobbie Chase, 1995–2001

- Tom Brevoort, 2007–2011[137]

- Axel Alonso, 2010 – January 2011[138]

Ownership

- Martin Goodman (1939–1968)

Parent corporation

- Magazine Management Co. (1968–1973)

- Cadence Industries (1973–1986)

- Marvel Entertainment Group (1986–1998)

- Marvel Enterprises, Inc. (1998–2005)

- Marvel Entertainment, Inc (2005–2009)

- Marvel Entertainment, LLC (2009–2023, a wholly owned subsidiary of The Walt Disney Company)

- Disney Publishing Worldwide (2023–present)

Offices

Located in New York City, Marvel has had successive headquarters:

- in the McGraw-Hill Building,[6] where it originated as Timely Comics in 1939[139]

- in suite 1401 of the Empire State Building[139]

- at 635 Madison Avenue (the actual location, though the comic books' indicia listed the parent publishing-company's address of 625 Madison Ave.)[139]

- 575 Madison Avenue;[139]

- 387 Park Avenue South[139]

- 10 East 40th Street[139]

- 417 Fifth Avenue[139]

- a 60,000-square-foot (5,600 m2) space in the Sports Illustrated Building at 135 W. 50th Street (October 2010—[106][140] present)

Productions

TV

Animated

| Series | Aired | Production | Distributor | Network | Episodes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Marvel Super Heroes | 1966 | Grantray-Lawrence Animation / Marvel Comics Group | Krantz Films | ABC | 65 |

| Fantastic Four | 1967–68 | Hanna-Barbera Productions / Marvel Comics Group | Taft Broadcasting | 20 | |

| Spider-Man | 1967–70 | Grantray-Lawrence Animation / Krantz Films / Marvel Comics Group | 52 | ||

| The New Fantastic Four | 1978 | DePatie-Freleng Enterprises / Marvel Comics Animation | Marvel Entertainment | NBC | 13 |

| Fred and Barney Meet the Thing | 1979 | Hanna-Barbera Productions / Marvel Comics Group | Taft Broadcasting | 13 (26 segments of The Thing) | |

| Spider-Woman | 1979–80 | DePatie-Freleng Enterprises / Marvel Comics Animation | Marvel Entertainment | ABC | 16 |

Market share

This section appears to be slanted towards recent events. (July 2017) |

In 2017, Marvel held a 38.30% share of the comics market, compared to its competitor DC Comics' 33.93%.[141] By comparison, the companies respectively held 33.50% and 30.33% shares in 2013, and 40.81% and 29.94% shares in 2008.[142]

Marvel characters in other media

Marvel characters and stories have been adapted to multiple media platforms. Some of these adaptations were produced by Marvel Comics and its sister company, Marvel Studios, while others were produced by companies licensing Marvel material.

Games

In June 1993, Marvel issued its collectable caps for milk caps game under the Hero Caps brand.[143] In 2014, the Marvel Disk Wars: The Avengers Japanese TV series was launched together with a collectible game called Bachicombat, a game similar to the milk caps game, by Bandai.[144]

Collectible card games

The RPG industry brought the development of the collectible card game (CCG) in the early 1990s which there were soon Marvel characters were featured in CCG of their own starting in 1995 with Fleer's OverPower (1995–1999). Later collectible card game were:

- Marvel Superstars (2010–?) Upper Deck Company

- ReCharge Collectible Card Game (2001–? ) Marvel

- Vs. System (2004–2009, 2014–) Upper Deck Company

- X-Men Trading Card Game (2000–?) Wizards of the Coast

- Marvel Champions: The Card Game (2019—present) Fantasy Flight Games, a Living Card Game[145]

Miniatures

- Marvel Crisis Protocol (Fall 2019—) Atomic Mass Games[146]

- HeroClix, WizKids

Role-playing

TSR published the pen-and-paper role-playing game Marvel Super Heroes in 1984. TSR then released in 1998 the Marvel Super Heroes Adventure Game which used a different system, the card-based SAGA system, than their first game. In 2003 Marvel Publishing published its own role-playing game, the Marvel Universe Roleplaying Game, that used a diceless stone pool system.[147] In August 2011 Margaret Weis Productions announced it was developing a tabletop role-playing game based on the Marvel universe, set for release in February 2012 using its house Cortex Plus RPG system.[148]

Video games

Video games based on Marvel characters go back to 1984 and the Atari 2600 game, Spider-Man. Since then several dozen video games have been released and all have been produces by outside licensees. In 2014, Disney Infinity 2.0: Marvel Super Heroes was released that brought Marvel characters to the existing Disney sandbox video game.

Films

As of the start of September 2015, films based on Marvel's properties represent the highest-grossing U.S. franchise, having grossed over $7.7 billion[149] as part of a worldwide gross of over $18 billion. As of 2024, the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) has grossed over $32 billion.

Live shows

- Spider-Man's Wedding (1987)

- Spider-Man On Stage (1999)

- Spider-Man Stunt Show: A Stunt Spectacular (2002–2004)

- Spider-Man Live! (2002–2003)

- The Marvel Experience (2014–)

- Marvel Universe Live! (2014–) live arena show

- Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark (2011–2014) a Broadway musical

Prose novels

Marvel first licensed two prose novels to Bantam Books, who printed The Avengers Battle the Earth Wrecker by Otto Binder (1967) and Captain America: The Great Gold Steal by Ted White (1968). Various publishers took up the licenses from 1978 to 2002. Also, with the various licensed films being released beginning in 1997, various publishers put out film novelizations.[150] In 2003, following publication of the prose young adult novel Mary Jane, starring Mary Jane Watson from the Spider-Man mythos, Marvel announced the formation of the publishing imprint Marvel Press.[151] However, Marvel moved back to licensing with Pocket Books from 2005 to 2008.[150] With few books issued under the imprint, Marvel and Disney Books Group relaunched Marvel Press in 2011 with the Marvel Origin Storybooks line.[152]

Television programs

Many television series, both live-action and animated, have based their productions on Marvel Comics characters. These include series for popular characters such as Spider-Man, Iron Man, the Hulk, the Avengers, the X-Men, Fantastic Four, the Guardians of the Galaxy, Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Luke Cage, Iron Fist, the Punisher, the Defenders, S.H.I.E.L.D., Agent Carter, Deadpool, Legion, and others. Additionally, a handful of television films, usually also pilots, based on Marvel Comics characters have been made.

Theme parks

Marvel has licensed its characters for theme parks and attractions, including Marvel Super Hero Island at Universal Orlando's Islands of Adventure[153] in Orlando, Florida, which includes rides based on their iconic characters and costumed performers, as well as The Amazing Adventures of Spider-Man ride cloned from Islands of Adventure to Universal Studios Japan.[154]

Years after Disney purchased Marvel in late 2009, Walt Disney Parks and Resorts plans on creating original Marvel attractions at their theme parks,[155][156] with Hong Kong Disneyland becoming the first Disney theme park to feature a Marvel attraction.[157][158] Due to the licensing agreement with Universal Studios, signed prior to Disney's purchase of Marvel, Walt Disney World and Tokyo Disney Resort are barred from having Marvel characters in their parks.[159] However, this only includes characters that Universal is currently using, other characters in their "families" (X-Men, Avengers, Fantastic Four, etc.), and the villains associated with said characters.[153] This clause has allowed Walt Disney World to have meet and greets, merchandise, attractions and more with other Marvel characters not associated with the characters at Islands of Adventures, such as Star-Lord and Gamora from Guardians of the Galaxy.[160][161]

Imprints

- Marvel Comics

- Marvel Press, joint imprint with Disney Books Group

- Icon Comics (creator owned)

- Infinite Comics

- Timely Comics

- MAX

- 20th Century Studios[162]

Disney Kingdoms

Marvel Worldwide with Disney announced in October 2013 that in January 2014 it would release its first comic book title under their joint Disney Kingdoms imprint Seekers of the Weird, a five-issue miniseries inspired by a never built Disneyland attraction Museum of the Weird.[116] Marvel's Disney Kingdoms imprint has since released comic adaptations of Big Thunder Mountain Railroad,[163] Walt Disney's Enchanted Tiki Room,[164] The Haunted Mansion,[165] two series on Figment[166][167] based on Journey Into Imagination.

Defunct

- Amalgam Comics

- CrossGen

- Curtis Magazines/Marvel Magazine Group

- Marvel Monsters Group

- Epic Comics (creator owned) (1982–2004)

- Malibu Comics (1994–1997)

- Marvel 2099 (1992–1998)

- Marvel Absurd

- Marvel Age/Adventures

- Marvel Books

- Marvel Edge

- Marvel Knights

- Marvel Illustrated

- Marvel Mangaverse

- Marvel Music

- Marvel Next

- Marvel Noir

- Marvel UK

- Marvel Frontier

- MC2

- New Universe

- Paramount Comics (co-owned with Viacom's Paramount Pictures)

- Razorline

- Star Comics

- Tsunami

- Ultimate Comics

See also

- List of comics characters which originated in other media

- List of magazines released by Marvel Comics in the 1970s

- List of current Marvel Comics publications

Notes

- ^ Apocryphal legend has it that in 1961, either Jack Liebowitz or Irwin Donenfeld of DC Comics (then known as National Periodical Publications) bragged about DC's success with the Justice League (which had debuted in The Brave and the Bold #28 [February 1960] before going on to its own title) to publisher Martin Goodman (whose holdings included the nascent Marvel Comics) during a game of golf.

However, film producer and comics historian Michael Uslan partly debunked the story in a letter published in Alter Ego #43 (December 2004), pp. 43–44

Irwin said he never played golf with Goodman, so the story is untrue. I heard this story more than a couple of times while sitting in the lunchroom at DC's 909 Third Avenue and 75 Rockefeller Plaza office as Sol Harrison and [production chief] Jack Adler were schmoozing with some of us … who worked for DC during our college summers.... [T]he way I heard the story from Sol was that Goodman was playing with one of the heads of Independent News, not DC Comics (though DC owned Independent News). … As the distributor of DC Comics, this man certainly knew all the sales figures and was in the best position to tell this tidbit to Goodman. … Of course, Goodman would want to be playing golf with this fellow and be in his good graces. … Sol worked closely with Independent News' top management over the decades and would have gotten this story straight from the horse's mouth.

Goodman, a publishing trend-follower aware of the JLA's strong sales, confirmably directed his comics editor, Stan Lee, to create a comic-book series about a team of superheroes. According to Lee in Origins of Marvel Comics (Simon and Schuster/Fireside Books, 1974), p. 16: "Martin mentioned that he had noticed one of the titles published by National Comics seemed to be selling better than most. It was a book called The [sic] Justice League of America and it was composed of a team of superheroes. … ' If the Justice League is selling ', spoke he, 'why don't we put out a comic book that features a team of superheroes?'"

References

- ^ a b Schedeen, Jesse (March 25, 2021). "Marvel Comics Shifts to New Distributor in Industry-Rattling Move – IGN". IGN. Archived from the original on March 25, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ "Hachette – Our Clients". Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c Daniels, Les (1991). Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics. New York: Harry N. Abrams. pp. 27 & 32–33. ISBN 0-8109-3821-9.

Timely Publications became the name under which Goodman first published a comic book line. He eventually created a number of companies to publish comics ... but Timely was the name by which Goodman's Golden Age comics were known... Marvel wasn't always Marvel; in the early 1940s the company was known as Timely Comics, and some covers bore this shield.

- ^ Sanderson, Peter (November 20, 2007). The Marvel Comics Guide to New York City. Gallery Books.

- ^ a b c Postal indicia in issue, per Marvel Comics #1 [1st printing] (October 1939) Archived November 3, 2014, at the Wayback Machine at the Grand Comics Database: "Vol.1, No.1, MARVEL COMICS, Oct, 1939 Published monthly by Timely Publications, ... Art and editorial by Funnies Incorporated..."

- ^ a b c d e Per statement of ownership, dated October 2, 1939, published in Marvel Mystery Comics #4 (Feb. 1940), p. 40; reprinted in Marvel Masterworks: Golden Age Marvel Comics Volume 1 (Marvel Comics, 2004, ISBN 0-7851-1609-5), p. 239

- ^ Bell, Blake; Vassallo, Michael J. (2013). The Secret History of Marvel Comics: Jack Kirby and the Moonlighting Artists at Martin Goodman's Empire. Fantagraphics Books. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-60699-552-5.

- ^ Writer-artist Bill Everett's Sub-Mariner had actually been created for an undistributed movie-theater giveaway comic, Motion Picture Funnies Weekly earlier that year, with the previously unseen, eight-page original story expanded by four pages for Marvel Comics #1.

- ^ a b Per researcher Keif Fromm, Alter Ego #49, p. 4 (caption), Marvel Comics #1, cover-dated October 1939, quickly sold out 80,000 copies, prompting Goodman to produce a second printing, cover-dated November 1939. The latter appears identical except for a black bar over the October date in the inside front-cover indicia, and the November date added at the end. That sold approximately 800,000 copies—a large figure in the market of that time. Also per Fromm, the first issue of Captain America Comics sold nearly one million copies.

- ^ Goulart, Ron (2000). Comic book culture: an illustrated history. Collectors Press, Inc. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-888054-38-5.. Preceding Captain America were MLJ Comics' the Shield and Fawcett Comics' Minute-Man.

- ^ "Marvel : Timely Publications (Indicia Publisher)" Archived January 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at the Grand Comics Database. "This is the original business name under which Martin Goodman began publishing comics in 1939. It was used on all issues up to and including those cover-dated March 1941 or Winter 1940–1941, spanning the period from Marvel Comics #1 to Captain America Comics #1. It was replaced by Timely Comics, Inc. starting with all issues cover-dated April 1941 or Spring 1941."

- ^ "GCD :: Story Search Results". comics.org. Archived from the original on December 11, 2007. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ^ A Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics. Smithsonian Institution/Harry N. Abrams. 1981.

- ^ Lee, Stan; Mair, George (2002). Excelsior!: The Amazing Life of Stan Lee. Fireside Books. p. 22. ISBN 0-684-87305-2.

- ^ Simon, Joe; with Simon, Jim (1990). The Comic Book Makers. Crestwood/II Publications. p. 208. ISBN 1-887591-35-4.

- ^ Simon, Joe (2011). Joe Simon: My Life in Comics. London, UK: Titan Books. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-1-84576-930-7.

- ^ Cover, All Surprise Comics #12 Archived June 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ "Seduction of the Innocent: More Anti-Comics Items". www.lostsoti.org. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- ^ "TheComicBooks.com - The History of Graphic Novels". March 8, 2021. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021.

- ^ V, Doc (February 6, 2011). "Timely-Atlas-Comics: Part 1: Fredric Wertham, Censorship & the Timely Anti-Wertham Editorials". Timely-Atlas-Comics. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- ^ Wright, Bradford W. (2001). Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8018-6514-5.

- ^ a b c "Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc.". International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 10. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale / St. James Press, via FundingUniverse.com. 1995. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ Marvel: Atlas [wireframe globe] (Brand) Archived January 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ "Marvel Indicia Publishers". comics.org. Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ Per Les Daniels in Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics, pp. 67–68: "The success of EC had a definite influence on Marvel. As Stan Lee recalls, 'Martin Goodman would say, "Stan, let's do a different kind of book," and it was usually based on how the competition was doing. When we found that EC's horror books were doing well, for instance, we published a lot of horror books'".

- ^ Boatz, Darrel L. (December 1988). "Stan Lee". Comics Interview. No. 64. Fictioneer Books. pp. 15–16.

- ^ Jones, Gerard. Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book (Basic Books, 2004).

- ^ "Stan the Man & Roy the Boy: A Conversation Between Stan Lee and Roy Thomas". Comic Book Artist. No. 2. Summer 1998. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009.

- ^ "Which was the first Marvel comic?". CGC Comic Book Collectors Chat Boards. August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- ^ Marvel : MC (Brand) Archived March 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ The Marvel Legacy of Jack Kirby. Marvel. 2015. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-785-19793-5.

- ^ "Fantastic Four". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ Roberts, Randy; Olson, James S. (1998). American Experiences: Readings in American History: Since 1865 (4 ed.). Addison–Wesley. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-321-01031-5.

Marvel Comics employed a realism in both characterization and setting in its superhero titles that was unequaled in the comic book industry.

- ^ Dunst, Alexander; Laubrock, Jochen; Wildfeuer, Janina (July 3, 2018). Empirical Comics Research: Digital, Multimodal, and Cognitive Methods. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-73388-5. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ Genter, Robert (2007). "With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility': Cold War Culture and the Birth of Marvel Comics". The Journal of Popular Culture. 40 (6): 953–978. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5931.2007.00480.x.

- ^ Comics historian Greg Theakston has suggested that the decision to include monsters and initially to distance the new breed of superheroes from costumes was a conscious one, and born of necessity. Since DC distributed Marvel's output at the time, Theakston theorizes that, "Goodman and Lee decided to keep their superhero line looking as much like their horror line as they possibly could," downplaying "the fact that [Marvel] was now creating heroes" with the effect that they ventured "into deeper waters, where DC had never considered going". See Ro, pp. 87–88

- ^ Benton, Mike (1991). Superhero Comics of the Silver Age: The Illustrated History. Dallas, Texas: Taylor Publishing Company. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-87833-746-0.

- ^ Benton, p. 38.

- ^ Howe, Sean (2012). Marvel Comics: The Untold Story. New York, NY: HarperCollins. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-06-199210-0.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (September 25, 2009). "Jack Kirby, the abandoned hero of Marvel's grand Hollywood adventure, and his family's quest". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "The Real Brand X". Time. October 31, 1960. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ^ "Branding Failure: The Rise and Fall of Marvel's Corner Box Art". YouTube. ComicTropes. August 31, 2021. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ Daniels, Les (September 1991). Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics, Harry N Abrams. p. 139.

- ^ Nyberg, Amy Kiste (1994). Seal of Approval: The Origins and History of the Comics Code. University Press of Mississippi. p. 170. ISBN 9781604736632.

- ^ a b c d e f Ro, Ronin (2004). Tales to Astonish: Jack Kirby, Stan Lee and the American Comic Book Revolution. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 179.

- ^ a b Lee, Mair, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Wickline, Dan (January 12, 2018). "Conan the Barbarian Returns to Marvel Comics – Bleeding Cool News". Bleeding Cool News And Rumors. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ^ Levitz, Paul (2010). 75 Years of DC Comics The Art of Modern Mythmaking. Taschen America. p. 451. ISBN 978-3-8365-1981-6.

Marvel took advantage of this moment to surpass DC in title production for the first time since 1957, and in sales for the first time ever.

- ^ Daniels, Marvel, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Rhoades, Shirrel (2008). A Complete History of American Comic Books. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 9781433101076.

- ^ Cooke, Jon B. (December 2011). "Vengeance, Incorporated: A history of the short-lived comics publisher Atlas/Seaboard". Comic Book Artist. No. 16. TwoMorrows Publishing. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ McMillan, Graeme (December 5, 2017). "Marvel Partners With Stitcher for Scripted 'Wolverine' Podcast". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 13, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ Both pencils and inks per UHBMCC; GCD remains uncertain on inker.

- ^ Bullpen Bulletins: "The King is Back! 'Nuff Said!", in Marvel Comics cover dated October 1975, including Fantastic Four #163

- ^ Specific series- and issue-dates in article are collectively per GCD and other databases given under References

- ^ Howe, Sean (August 20, 2014). "After His Public Downfall, Sin City's Frank Miller Is Back (And Not Sorry)". Wired. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on January 22, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ^ "Marvel Focuses On Direct Sales". The Comics Journal (59): 11–12. October 1980.

- ^ "Harvey Sues Marvel Star Comics, Charges Copyright Infringement", The Comics Journal #105 (Feb. 1986), pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b c "Marvel Reaches Agreement to Emerge from Bankruptcy". The New York Times. July 11, 1997. p. D3. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Clive Barker official site: Comics". Clivebarker.com. November 28, 1999. Archived from the original on May 13, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "Independent Heroes from the USA: Clive Barker's Razorline". Internationalhero.co.uk. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "Bye Bye Marvel; Here Comes Image: Portacio, Claremont, Liefeld, Jim Lee Join McFarlane's New Imprint at Malibu". The Comics Journal (48): 11–12. February 1992.

- ^ Mulligan, Thomas S. (February 19, 1992). "Holy Plot Twist : Marvel Comics' Parent Sees Artists Defect to Rival Malibu, Stock Dive". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on May 10, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

- ^ Ehrenreich, Ben (November 11, 2007). "Phenomenon – Comic Genius?". The New York Times magazine. Archived from the original on August 7, 2013. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ Reynolds, Eric. "The Rumors are True: Marvel Buys Malibu", The Comics Journal #173 (December 1994), pp. 29–33.

- ^ "News!" Indy magazine #8 (1994), p. 7.

- ^ "Scott Rosenberg". Wizard World. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Webber, Tim (November 12, 2019). "The Ultraverse: How Marvel Absorbed the Malibu Comics World". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ "Marvel allies with Harvey Comics - UPI Archives". UPI. Archived from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Duin, Steve and Richardson, Mike (ed.s) "Capital City" in Comics Between the Panels (Dark Horse Publishing, 1998) ISBN 1-56971-344-8, p. 69

- ^ Rozanski, Chuck (n.d.). "Diamond Ended Up With 50% of the Comics Market". MileHighComics.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ^ "Diamond Comic Distributors acquires Capital City Distribution; Comic distribution industry stabilized by purchase". bNet: Business Wire via Findarticles.com. July 26, 1996. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ^ "Hello Again: Marvel Goes with Diamond", The Comics Journal #193 (February 1997), pp. 9–10.

- ^ Duin, Steve and Richardson, Mike (ed.s) "Diamond Comic Distributors" in Comics Between the Panels (Dark Horse Publishing, 1998) ISBN 1-56971-344-8, p. 125-126

- ^ Huckabee, Tyler (June 15, 2021). "Meet the 1990s Marvel Christian Superhero Disney Doesn't Want You to Know About". RELEVANT. Archived from the original on May 21, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ "GCD :: Brand Emblem :: Marvel Comics; Nelson". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ Miller, John Jackson. "Capital Sale Tops Turbulent Year: The Top 10 Comics News Stories of 1996". CBGXtra. Archived from the original on November 7, 2007. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ^ Raviv, Dan (2001). Comic War: Marvel's Battle for Survival. Heroes Books. ISBN 978-0-7851-1606-6.

- ^ a b McMillan, Graeme. Page 10. "Leaving an Imprint: 10 Defunct MARVEL Publishing Lines" Archived October 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Newsarama (January 10, 2013).

- ^ Glaser, Brian. "Q+A: Joe Quesada". Visual Arts Journal. School of Visual Arts. Fall 2011. pp. 50–55.

- ^ Marnell, Blair (June 23, 2020). "The Legacy of Marvel Knights Black Panther". Marvel. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Dietsch, TJ (July 28, 2017). "Inhuman Nature: Marvel Knights". Marvel. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Capitanio, Adam (August 13, 2014). "Race and Violence from the "Clear Line School": Bodies and the Celebrity Satire of X-Statix". In Darowski, Joseph J. (ed.). The Ages of the X-Men: Essays on the Children of the Atom in Changing Times. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 158. ISBN 9780786472192.

- ^ Ching, Albert (January 18, 2012). "Looking Back on X-FORCE and X-STATIX with Mike Allred". Newsarama. Archived from the original on August 20, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ "X-Force #116 To Be Non-Code". ICv2. April 27, 2001. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Marvel Considers the Comics Code". ICv2. May 8, 2001. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Walton, Michael (2019). The Horror Comic Never Dies: A Grisly History. Jefferson (North Carolina): McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-4766-7536-7.

- ^ Rosemann, Bill (July 5, 2001). "Marvel's New Ratings System... Explained!". Comic Book Resources (Press release). Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ^ Harn, Darby (May 24, 2022). "10 Best Marvel MAX Comic Books". ScreenRant. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Marvel Announces Spider-Man And Super Heroes All Ages Series". ComicBook.com. January 13, 2010. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Lawson, Corrina (May 11, 2011). "Comic Spotlight on Marvel Adventures Thor". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Abraham Riesman (May 25, 2015). "The Secret History of Ultimate Marvel, the Experiment That Changed Superheroes Forever". Vulture. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ "Franchises: Marvel Comics". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ^ "Guiding Light Comes to Comics! | Marvel.com News". Marvel.com. Archived from the original on May 12, 2010. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ^ Gustines, George (October 31, 2006). "Pulpy TV and Soapy Comics Find a Lot to Agree On". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 17, 2018. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ "Marvel Universe wiki". Marvel.com. June 11, 2007. Archived from the original on April 29, 2010. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ^ Colton, David (November 12, 2007). "Marvel Comics Shows Its Marvelous Colors in Online Archive". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 23, 2011. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ MacDonald, Heidi (December 11, 2007). "Marvel, Del Rey Team for Manga X-men". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ^ Doran, Michael (April 3, 2009). "C.B. Cebulski on Marvel's Closed Open Submissions Policy". Newsarama. Archived from the original on April 6, 2009. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

- ^ Frisk, Andy (June 6, 2009). "Marvel Mystery Comics 70th Anniversary Special #1 (review)". ComicBookBin. Archived from the original on August 12, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ^ "Celebrate Marvel's 70th Anniversary with Your Local Comic Shop". Marvel Comics press release via Comic Book Resources. July 31, 2009. Archived from the original on August 3, 2009.

- ^ "Fiscal Year 2009 Annual Financial Report And Shareholder Letter" (PDF). The Walt Disney Company. November 23, 2015 [2009-10-03 USSEC Form 10-K]. p. 78. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2018 – via Google API.

- ^ Wilkerson, David B. (August 31, 2009). "Disney to acquire Marvel Entertainment for $4B". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ Siklos, Richard (October 13, 2008). "Spoiler alert: Comic books are alive and kicking". CNN. Archived from the original on March 17, 2010. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ^ "Marvel Goes With Hachette". ICV2. May 12, 2010. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ a b "Marvel to move to new, 60,000-square-foot offices in October". Comic Book Resources. September 21, 2010. Archived from the original on October 24, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Reid, Calvin (December 21, 2010). "Marvel Revives CrossGen with New Creators, New Stories". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ "'Cars' Creative Team On Marvel's Pixar Move". Comic Book Resources. February 17, 2011. Archived from the original on November 19, 2011. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ "Marvel Ends Current Kids Line of Comics". Comic Book Resources. December 19, 2011. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ "Marvel Launches All-Ages "Avengers" & "Ultimate Spider-Man" Comics". Comic Book Resources. January 24, 2012. Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ "Marvel, circus company join forces for superhero arena show". Los Angeles Times. March 13, 2013. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- ^ "Marvel Wants You To Join The ReEvolution". Comic Book Resources. March 12, 2012. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ Alonso, Axel (August 17, 2012). "Axel-In-Charge: "Avengers Vs. X-Men's" Final Phase". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ Morse, Ben (July 5, 2012). "Marvel NOW!". Marvel Comics. Archived from the original on October 3, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ Sands, Rich. (April 12, 2013) First Look: The Once Upon a Time Graphic Novel Archived November 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. TV Guide.com. Accessed on November 4, 2013.

- ^ a b "Marvel, Disney unveil 1st comic under new imprint". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Associated Press. October 8, 2013. Archived from the original on October 18, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- ^ "'Star Wars' Comics Go to Marvel in 2015, Dark Horse Responds". Newsarama. January 3, 2014. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ Whitbrook, James (June 4, 2015). "Marvel Will Launch An "All-New, All-Different" Universe This September". io9. Archived from the original on June 23, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ McMillan, Graeme (August 25, 2017). "Comic Store Owners Refusing to Carry 'Marvel Legacy' Issues". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ McMillan, Graeme (December 28, 2017). "DC Takes Over a Declining Market: Which Comics Sold Best in 2017". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ León, Concepción de (March 1, 2019). "Digital Book Platform Serial Box Will Partner With Marvel to Release New Stories". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ Johnston, Rich (April 17, 2020). "Confirmed: Diamond Comics Makes Plan to Return to Distribution in May". Bleeding Cool. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ Thielman, Sam (April 20, 2020). "'This is beyond the Great Depression': will comic books survive coronavirus?". The Guardian. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ Arrant, Chris (January 7, 2021). "Canceled or..? The nine 2020 Marvel titles that never came out – and the latest". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on May 19, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks (March 29, 2023). "Disney Lays Off Ike Perlmutter, Chairman of Marvel Entertainment". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 29, 2023. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ Vary, Adam (March 29, 2023). "Disney Absorbs Marvel Entertainment Amid Layoffs, Dismisses Chairman Ike Perlmutter". Variety. Archived from the original on March 29, 2023. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ Johnston, Rich (June 17, 2024). "Marvel Comics Gets A Brand New Logo (Update)". Bleeding Cool. Archived from the original on June 17, 2024. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Jackson, Gordon (June 17, 2024). "Marvel Comics' New Logo Kind of Sucks, Actually". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on June 17, 2024. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Rhoades, Shirrel (2008). A complete history of American comic books. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing. pp. x–xi. ISBN 978-1-4331-0107-6. Archived from the original on May 27, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Gilroy, Dan (September 17, 1986). "Marvel Now a $100 Million Hulk: Marvel Divisions and Top Execs". Variety. p. 81. Archived from the original (jpeg) on February 14, 2012.

- ^ Weiland, Jonah (October 15, 2003). "Marvel confirms Buckley as new Publisher". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- ^ a b Viscardi, James (January 16, 2018). "Marvel Hires John Nee As Publisher (EXCLUSIVE)". Marvel. Archived from the original on January 8, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ Kit, Borys (January 18, 2017). "Dan Buckley Named President of Marvel Entertainment (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Interview: Carl Potts". PopImage.com. May 2000. Archived from the original on May 25, 2011.

- ^ McMillan, Graeme (November 17, 2017). "Marvel Names New Editor-in-Chief as Axel Alonso Exits". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 27, 2018. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ "1976–1979". DC Timeline. dccomicsartists.com. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ Frankenhoff, Brent (January 4, 2011). "Marvel editors Axel Alonso, Tom Brevoort promoted". Comics Buyer's Guide Extra. Archived from the original on November 7, 2015. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ^ Phegley, Kiel (January 4, 2011). "Alonso Named Marvel Editor-In-Chief". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sanderson, Peter. The Marvel Comics Guide to New York City Archived June 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, (Pocket Books, 2007) p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4165-3141-8

- ^ Turner, Zake (December 21, 2010). "Where We Work". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on December 28, 2011.

- ^ Miller, John. "2017 Comic Book Sales to Comics Shops". Comichron. Archived from the original on January 23, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

Share of Overall Units—Marvel 38.30%, DC 33.93%; Share of Overall Dollars—Marvel 36.36%, DC 30.07%

- ^ "Big Two Comic Publishers Lose Share". ICv2. January 8, 2014. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ Routhier, Ray (July 26, 1993). "Will Cardboard Caps From Milk Bottles Become Cream Of All". Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on September 25, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- ^ "Marvel Disk Wars: The Avengers Anime & Game's 1st Promo Streamed". Anime News Network. February 10, 2014. Archived from the original on May 7, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ Griepp, Milton (August 1, 2019). "Fantasy Flight to Launch Marvel LCG". icv2.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ "Atomic Mass Games Unveils 'Marvel Crisis Protocol Miniatures Game'". icv2.com. August 4, 2019. Archived from the original on December 11, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ Kim, John H. "RPG Encyclopedia: M". RPG Encyclopedia. darkshire.net. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ^ Holochwost, George (August 5, 2011). "Gen Con: New Marvel Comics RPG Games Announced by Margaret Weis Productions". MTV.com. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "Franchise Index". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 1, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- ^ a b DeCandido, Keith R.A. "Marvel Comics in Prose: An Unofficial Guide". SFF.net. Archived from the original on August 6, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Weiland, Jonah (May 26, 2004). "Marvel Announces Creation of New Prose Imprint, Marvel Press". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2011.

- ^ Alverson, Brigid (July 15, 2011). "SDCC '11 | Disney to unveil Marvel Press imprint at San Diego". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on August 18, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ a b "Marvel Agreement between MCA Inc. and Marvel Entertainment Group". sec.gov. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ^ "Universal's Islands of Adventures: Marvel Super Hero Island (official site)". Archived from the original on June 20, 2009.

- ^ Chmielewski, Dawn C. (March 14, 2012). "Walt Disney plans to deploy Marvel superheroes at its theme parks". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ "Disney Parks Might Soon Add Marvel Characters". Huffington Post. March 20, 2012. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ Chu, Karen (October 8, 2013). "Hong Kong Disneyland to Open 'Iron Man' Experience in 2016". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 28, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ^ John Tsang (February 27, 2013). "The 2013–14 Budget – Promoting Tourism Industry". Hong Kong Government. Archived from the original on January 17, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ Munarriz, Rick (October 18, 2015). "Disney is Taking Too Long to Add Marvel to Disneyland and Disney World". The Motley Fool. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "Guardians of the Galaxy theme park characters appear for first time as Walt Disney World welcomes Marvel". Inside the Magic. August 24, 2014. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ^ "Exclusive 'Guardians of the Galaxy' Sneak Peek Debuts July 4 at Disney Parks". Disney Parks Blog. July 3, 2014. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ^ Couch, Aaron (March 3, 2023). "Marvel Launches 20th Century Studios Imprint with 'Planet of the Apes' Comic (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ^ Lee, Banks (November 16, 2014). "Big Thunder Mountain Railroad to become next Disney Kingdoms Marvel comic". Attractions Magazine. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ "First look at Disney Kingdoms' new Enchanted Tiki Room comic book". Attractions Magazine. September 12, 2016. Archived from the original on November 9, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ Lee, Banks (February 26, 2016). "Preview of Marvel's Haunted Mansion #1 comic". Attractions Magazine. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ Lovett, Jamie (September 6, 2017). "Disney Kingdoms' Figment #1 Preview: Spark Your Imagination". ComicBook.com. Archived from the original on July 11, 2014. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ Lee, Banks (June 28, 2015). "Dreamfinder and Figment return in sequel to Marvel comic book series". Attractions Magazine. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

Further reading

- George, Milo (2001). Jack Kirby: The TCJ Interviews. Fantagraphics Books. ISBN 1-56097-434-6.

- Howe, Sean (2012). Marvel Comics: the Untold Story. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-199210-0.

- Jones, Gerard (2004). Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-03657-0.

- Lupoff, Dick; Thompson, Don (1997). All in Color for a Dime. Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-498-5.

- Steranko, James (1971). The Steranko History of Comics. Vol. 1. Supergraphics. ISBN 0-517-50188-0.

External links

- Official website

- Vassallo, Michael J. (2005). "A Timely Talk with Allen Bellman". Comicartville.com. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 17, 2010..

- Complete Marvel Reading Order from Travis Starnes

- Marvel Comics

- 1939 establishments in New York City

- American companies established in 1939

- Culture of the United States

- Comic book publishing companies of the United States

- Comics publications

- Companies that filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1996

- Disney comics publishers

- Marvel Entertainment

- Publishing companies based in New York City

- Publishing companies established in 1939

- The Walt Disney Company subsidiaries